- Hatsumode! First visit to Meiji jingu Shrine: How to avoid crowds

- Meiji jingu Shrine is the shrine with the largest number of New Year's visitors in Japan every year. We will introduce ways to avoid crowds and visit the shrine smoothly.

Last updated:

Shinto is one of Japan’s oldest religious traditions and a major source of Japanese spirituality. At the heart of Shinto is the belief that deities, or kami, dwell in nature and in the land itself. For this reason, Japan has long been home to countless sacred places, and Shinto has deeply influenced everyday life and culture.

Among these sacred places, you often hear the words “Jinja,” “Jingu,” and “Taisha.” At first glance they may look similar, but each has a different meaning. Jingu usually refers to shrines that enshrine the imperial ancestral deities, while Taisha is an honorific title that indicates particularly high status. Understanding these differences can make your shrine visits more meaningful and enjoyable.

In this article, we explain the differences between Jinja, Jingu, and Taisha in an easy-to-understand way and introduce representative shrines from around Japan. Use it as a guide when planning a trip to experience Japan’s faith and culture.

A Jinja (Shinto shrine) is a general term for facilities where deities are enshrined according to Shinto belief. From local guardian deities to historical figures, a wide variety of kami are worshipped, and each region holds its own festivals and rituals. Shrine priests are people who have obtained official qualifications from the Association of Shinto Shrines, and in many shrines the role is passed down through the family. There are around 80,000 shrines across Japan, and they are familiar places closely connected to people’s daily lives.

Shrine names include not only “〇〇 Jinja” but also “〇〇 Jingu,” “〇〇-gu,” and “〇〇 Taisha.” All of these are types of shrines. Let’s look at what makes each of them different.

The words that appear at the end of shrine names, such as “Jingu,” “gu,” and “Taisha,” are called shago, or shrine titles. The title used depends on the shrine’s history and on which deity is enshrined. Below is an overview of what each title means and its main characteristics.

A Jingu is a shrine that enshrines the imperial ancestral deities or deities connected to the Imperial Family. The best-known example is Ise Jingu. Ise Jingu is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami and is regarded as the most prestigious shrine in Japan. At Jingu shrines, rituals and worship are closely tied to the Imperial Family, and at Ise Jingu the chief priest (sai-shu) is a former female member of the Imperial Family. There are only a little over twenty shrines in Japan that bear the title Jingu, and all of them have a deep relationship with the Imperial Household.

There is also an even more exalted title, “Daijingu,” used for particularly important Jingu shrines. Examples include Kotaijingu (the Inner Shrine of Ise Jingu), Toyouke Daijingu (the Outer Shrine), and Tokyo Daijingu, which was founded as a distant worship hall for Ise Jingu.

The title “gu” is mainly used for shrines that enshrine emperors, members of the Imperial Family, or notable historical figures as deities. Examples include Nikko Toshogu, which enshrines Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the Tenmangu shrines such as Dazaifu Tenmangu and Kitano Tenmangu, which are dedicated to Sugawara no Michizane, the deity of learning. While gu shrines do not necessarily have the same level of prestige as Jingu shrines, they occupy a special position distinct from ordinary Jinja.

Taisha is a title that signifies particularly high status among shrines. Historically, the word “Ooyashiro” or “Taisha” referred exclusively to Izumo Taisha. During the Meiji period, a formal shrine ranking system was introduced, classifying shrines as Kanpei Taisha, Kokuhei Taisha, and so on. This system was abolished after World War II, and many prominent shrines began using “Taisha” in their names. Today, important historical and religious sites such as Izumo Taisha, Kasuga Taisha, Sumiyoshi Taisha, and Suwa Taisha are known by this title.

Shrines with the Taisha title are often dedicated to deities central to a region or to Japanese mythology as a whole, and their festivals and rituals are typically major events celebrated locally or nationwide.

Jingu and gu are titles that reflect “which deity is enshrined.” Jingu shrines enshrine the imperial ancestral deities or emperors, while gu shrines enshrine members of the Imperial Family or historic figures.

Taisha, on the other hand, is a title that indicates a shrine’s high status rather than the type of deity enshrined, so it is a different kind of classification.

In a broad sense, however, Jingu, gu, and Taisha are all types of Jinja. Together they form an essential part of Japan’s religious traditions and cultural heritage.

Jingu shrines are the most prestigious class of shrines, enshrining the imperial ancestral deities or deities closely related to the Imperial Family. Only about twenty shrines across Japan use the Jingu title, and each is deeply intertwined with Japanese history. Below are five of the most representative Jingu shrines.

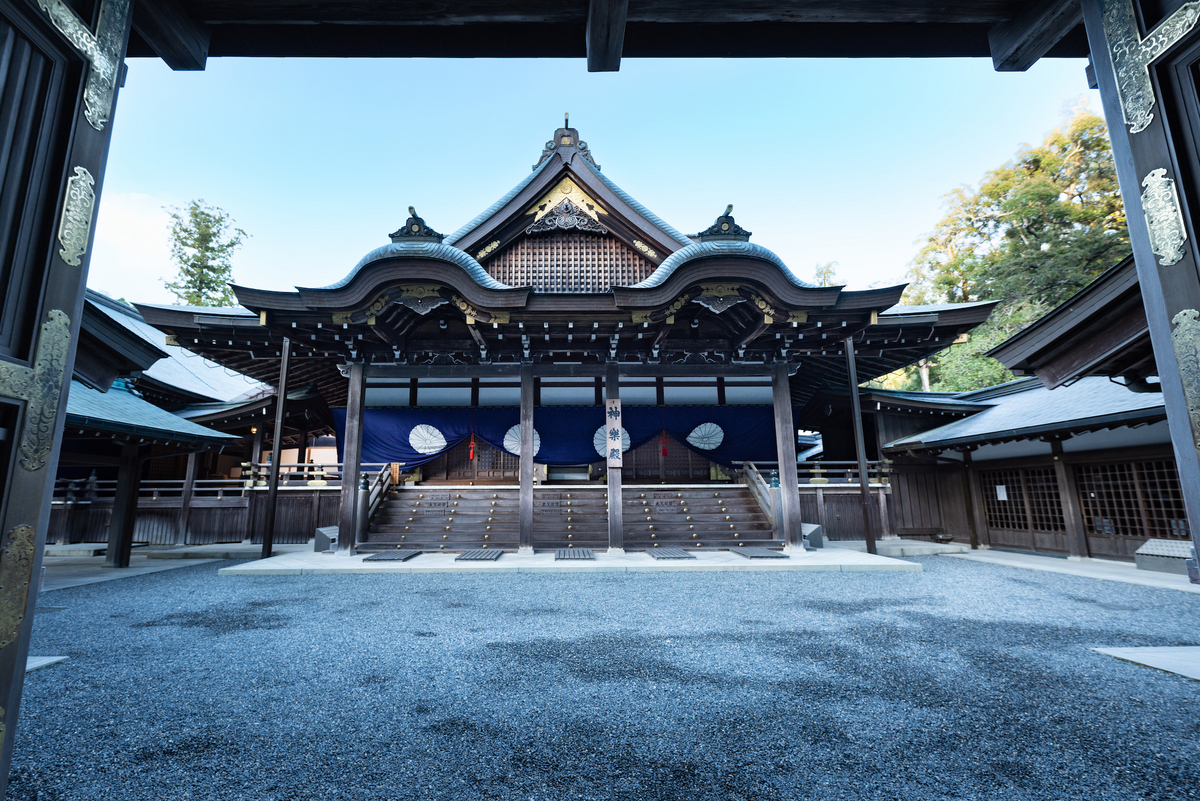

Located in Shibuya, Tokyo, Meiji Jingu Shrine is dedicated to Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken. It was founded in 1920 and, despite being in the heart of Tokyo, is surrounded by an expansive forest of about 700,000 square meters. Meiji Jingu welcomes more New Year’s visitors than any other shrine in Japan, with over three million people coming for hatsumode every year. As a Jingu shrine closely associated with the Imperial Family, it attracts worshippers from Japan and abroad and is one of Tokyo’s most iconic sacred sites.

Read more about Meiji Jingu Shrine

Located in Ise City, Mie Prefecture, Ise Jingu Shrine is dedicated to Amaterasu Omikami, the imperial ancestral deity, and is regarded as the most revered shrine in Japan. Its official name is simply “Jingu,” and the complex centers on the Inner Shrine (Kotaijingu) and Outer Shrine (Toyouke Daijingu), along with a total of 125 subsidiary shrines. Tradition holds that it was founded around 2,000 years ago, and for over 1,300 years the buildings have been completely rebuilt every 20 years in the Shikinen Sengu ritual. Known historically as the destination of the “Oise-mairi” pilgrimage, Ise Jingu still attracts around eight million worshippers each year.

Located in Kashima City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Kashima Jingu Shrine is dedicated to Takemikazuchi-no-Okami, a deity associated with martial arts. According to tradition, it was founded in the first year of Emperor Jimmu’s reign (660 BCE) and is considered one of Japan’s oldest shrines. It is the head shrine of roughly 600 Kashima shrines nationwide and historically garnered strong devotion from samurai. Highlights on the grounds include a national treasure straight sword and the Kaname-ishi, a “keystone” said to subdue earthquakes. The phrase “Kashima-dachi,” meaning to set off on a journey, is said to originate from this shrine, which has long been regarded as a place to pray before departing.

Located in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture, Atsuta Jingu Shrine enshrines the sacred sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, one of the Three Imperial Regalia. Tradition dates its founding to the year 113, giving it a history of roughly 1,900 years. Revered since ancient times by both the Imperial Family and powerful warlords, it is ranked just below Ise Jingu in prestige. The shrine is also famous for Oda Nobunaga’s visit to pray for victory before the Battle of Okehazama. The expansive grounds, known as “Atsuta no Mori,” form a green oasis in the city, and around 6.5 million worshippers visit each year.

Located in Nichinan City, Miyazaki Prefecture, Udo Jingu Shrine is a rare shrine whose main hall stands inside a cave on cliffs facing the Hyuga-nada Sea. The enshrined deity is Ugayafukiaezu-no-Mikoto, the father of Emperor Jimmu, and the shrine is widely worshipped as a place to pray for love, safe childbirth, and childrearing. Its approach slopes downward toward the main hall in the unique style known as a “downhill shrine” (kudari-miya), and Udo Jingu is considered one of Japan’s three famous downhill shrines. A popular custom is “undama-nage,” in which visitors throw small clay balls called undama at a hollow in a rock shaped like a turtle; getting one to land in the hollow is said to grant a wish.

Jinja are the most common type of Shinto shrine, where deities are enshrined and worshipped. Besides names ending in “〇〇 Jinja,” there are many shrines titled “〇〇-gu” or “〇〇 Tenmangu,” but all are types of Jinja. Below are five particularly famous shrines that represent this category.

Located in Nikko City, Tochigi Prefecture, Nikko Toshogu Shrine enshrines Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first shogun of the Edo shogunate. It was founded in 1617 and was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. The shrine is famous for its lavish architecture, including the Three Wise Monkeys that “see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil,” and the richly decorated Yomeimon Gate. Showcasing the finest craftsmanship and artistry of the Edo period, it is one of Japan’s most iconic shrine complexes.

Located in Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto City, Yasaka Jinja Shrine is dedicated to Susanoo-no-Mikoto as its main deity. Tradition dates its founding to the year 656, and it has long been affectionately known as “Gion-san” by the people of Kyoto. It is the head shrine of around 2,300 Yasaka and Gion shrines across Japan and is revered as a deity of warding off misfortune and epidemics. The Gion Matsuri, held every July, is one of Japan’s three great festivals and has been a hallmark of Kyoto’s summers for over a thousand years. The shrine stands at the eastern end of Shijo Street and, along with Kiyomizu-dera, is one of the major attractions in the Higashiyama area.

Located in Kamigyo Ward, Kyoto City, Kitano Tenmangu Shrine is dedicated to Sugawara no Michizane, renowned as the deity of learning. Founded in 947, it is regarded as the head shrine of roughly 12,000 Tenmangu and Tenjin shrines nationwide. The shrine is also famous for its plum blossoms; around 1,500 trees come into bloom from February to March. During exam season, countless students visit to pray for academic success.

Located on Miyajima Island in Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, Itsukushima Jinja Shrine is globally famous for its giant torii gate rising from the sea. Tradition states that it was first founded during the reign of Empress Suiko (593), and the current shrine complex was developed under Taira no Kiyomori. In 1996, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As the symbol of “Aki no Miyajima,” one of Japan’s three most scenic views, the shrine draws visitors from around the world.

Located in Dazaifu City, Fukuoka Prefecture, Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine was built over the grave of Sugawara no Michizane. The current main hall dates back to 919, and along with Kitano Tenmangu it is revered as one of the principal Tenmangu shrines in Japan. Dedicated to the deity of learning and the arts, it attracts around ten million worshippers each year. The shrine is also known for the legend of the flying plum tree and for its local specialty, umegae-mochi rice cakes sold along the approach.

Taisha is a title that indicates especially high status among shrines. Originally, the word referred exclusively to Izumo Taisha, but after the abolition of the state shrine ranking system following World War II, leading shrines across Japan began to adopt the Taisha title. Here we introduce five of the most representative Taisha shrines.

Located in Nara City, Nara Prefecture, Kasuga Taisha Shrine enshrines four deities: Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto, Futsunushi-no-Mikoto, Ame-no-Koyane-no-Mikoto, and Hime-gami. It was founded in 768 to protect the capital at Heijo-kyo and prospered as the tutelary shrine of the influential Fujiwara clan. Kasuga Taisha is the head shrine of around 3,000 Kasuga shrines nationwide and was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998. The grounds feature about 3,000 stone lanterns and roughly 1,000 hanging lanterns, and the fantastic display when all are lit during the biannual Mantoro festival captivates visitors.

Located in Izumo City, Shimane Prefecture, Izumo Taisha Shrine is dedicated to Okuninushi-no-Okami. Its origins trace back to the age of myth, and it is regarded as one of Japan’s oldest shrines. Widely known as a powerful shrine for marriage and relationships, it is said that all the deities of Japan gather in Izumo during the tenth month of the lunar calendar. For this reason, while most of Japan calls this month “Kannazuki” (the month without gods), Izumo calls it “Kamiarizuki” (the month when the gods are present). The main hall, built in the ancient Taisha-zukuri architectural style, is designated a National Treasure. The massive shimenawa rope hanging at the worship hall, about 13 meters long and weighing around five tons, has become a symbol of Izumo Taisha.

Located around Lake Suwa in Nagano Prefecture, Suwa Taisha Shrine is dedicated to Takeminakata-no-Kami and Yasakatome-no-Kami. It is the head shrine of roughly 25,000 Suwa shrines across Japan and is considered one of the country’s oldest shrines, with origins predating even the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki chronicles. Suwa Taisha has a distinctive structure consisting of four shrines—Upper Shrine (Honmiya and Maemiya) and Lower Shrine (Harumiya and Akimiya)—facing each other across Lake Suwa. Every seven years, the famous Onbashira Festival is held, during which enormous logs are hauled down from the mountains and erected at the shrines in a spectacular and daring ritual. This festival is counted among Japan’s three great eccentric festivals.

Located in Fushimi Ward, Kyoto City, Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine is dedicated to Inari Okami. Founded in 711, it is the head shrine of roughly 30,000 Inari shrines nationwide and has long been revered by merchants and farmers as a deity of business prosperity and bountiful harvests. The mountain paths of sacred Mt. Inari are lined with around 10,000 vermilion torii gates known collectively as the Senbon Torii, creating one of the most iconic and photogenic views in Japan. Instead of guardian lion-dogs, foxes serve as divine messengers and stand watch throughout the grounds. The shrine is extremely popular with overseas visitors and welcomes about ten million worshippers each year.

Read more about Fushimi Inari Taisha

Located in Osaka City, Osaka Prefecture, Sumiyoshi Taisha Shrine is the head shrine of around 2,300 Sumiyoshi shrines across Japan. Tradition dates its founding to the year 211, and it enshrines the three Sumiyoshi deities—Sokotsutsuno-wo-no-Mikoto, Nakatsutsuno-wo-no-Mikoto, Uwatsutsuno-wo-no-Mikoto—along with Empress Jingu. The main hall showcases the Sumiyoshi-zukuri style, one of the oldest forms of shrine architecture, and is designated a National Treasure. As a shrine of maritime safety and business prosperity, it has long been cherished by the people of Osaka.

Read more about Sumiyoshi Taisha Shrine

Jingu, Jinja, and Taisha are central symbols of Japanese belief and culture and have captivated people’s hearts since ancient times.

As we have seen, Jingu shrines enshrine the imperial ancestral deities, gu shrines (including many Tenmangu) enshrine members of the Imperial Family or historic figures, and Taisha is a title that indicates particularly high status. All of them belong to the broader category of Jinja, yet each type of shrine has its own unique origins and roles.

Ise Jingu’s solemn atmosphere, the familiar presence of local shrines in each neighborhood, the mythic grandeur of Izumo Taisha—understanding what makes each shrine special will help you appreciate shrine visits on a deeper level.

Japan is home to roughly 80,000 shrines, each with its own history and stories. Use this guide as a starting point and set out on a journey to explore Japan’s shrines while experiencing the country’s living faith and culture.