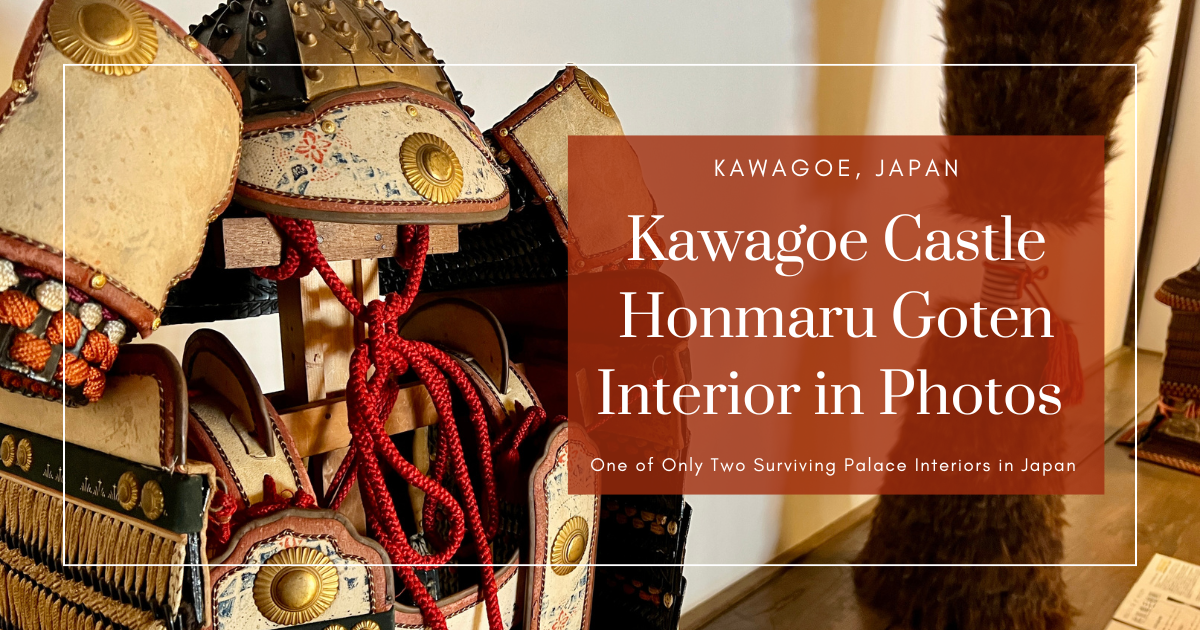

- Kawagoe Castle Honmaru Palace Guide: Must-See Highlights and Fascinating Finds

- Discover Kawagoe Castle Honmaru Palace through its must-see highlights and hidden stories. A journey into history, craftsmanship, and unexpected discoveries.

Last updated:

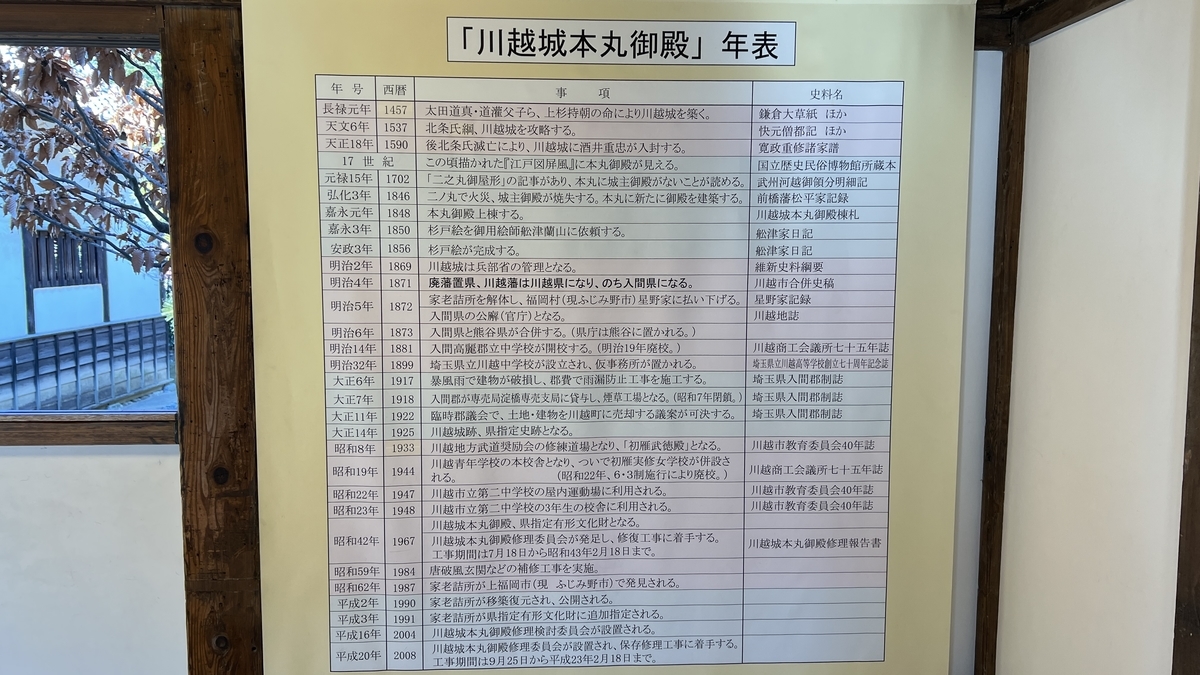

Only two Honmaru palace buildings from the time of construction still exist in Japan: Kochi Castle’s Honmaru Goten and this Kawagoe Castle Honmaru Goten.

During the Edo period, it is said that shoguns stayed here when they came for falconry. Tokugawa Ieyasu is believed to have visited Kawagoe eight times, and Tokugawa Iemitsu nine times.

This article takes you on a rare photographic journey through the interior of Kawagoe Castle’s Honmaru Goten.

The front is symmetrical and dignified, with a large and imposing entrance.

The north side, where the attendants’ quarters and the Nakano-kuchi gate are located, is beautifully refined.

This is the northwest side, viewed from behind the main entrance. On the right is the karō (chief retainer) office.

Next to the entrance, you’ll find a kushigata-bei, a traditional comb-shaped wall.

The grand entrance is supported by thick 24cm square columns and features a massive traditional tiled roof. The opening spans 3 ken (about 5.45 meters) wide.

Back then, only feudal lords or higher—meaning only the shogun—could use this entrance. Even the domain lord used the Nakano-kuchi gate. The formality is evident.

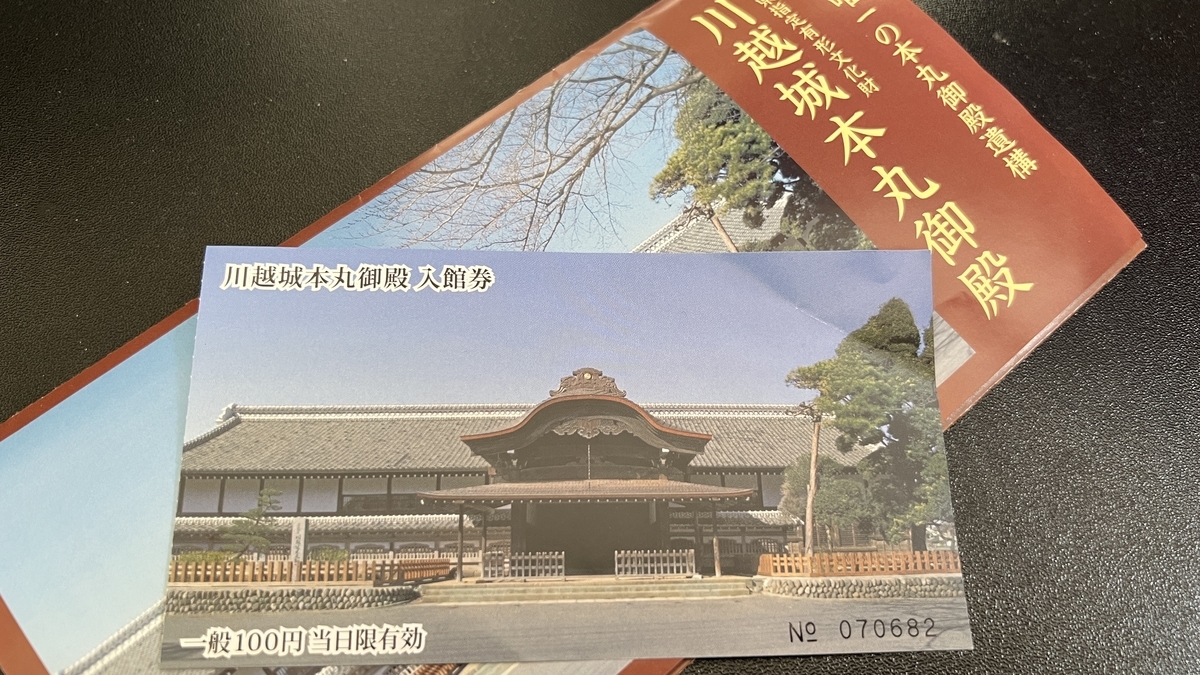

Just after stepping into the entrance, there’s a reception where adults pay a 100 yen admission fee to enter the Honmaru Goten.

The current layout of Kawagoe Castle’s Honmaru Goten looks like this. A full tour takes about 20–30 minutes at a relaxed pace.

The corridors encircle the rooms—look closely at the flooring, as different types of wood are used depending on the section.

The eastern side, where the entrance and Nakano-kuchi gate are, uses durable and dense zelkova wood. Meanwhile, the southern and western areas use soft and warm spruce or pine.

This separation reflects the distinction between formal public spaces and relaxed private ones, showcasing the meticulous attention to detail and the values of the samurai society at the time.

The flooring is well-maintained thanks to those who preserve it.

However, the floors get cold in winter, so consider bringing your own slippers if you want to explore slowly.

The quiet and serene atmosphere truly matches the word “contemplative.”

The “envoys” here were those waiting for an audience with the feudal lord. This room served as their waiting area.

The transom has a somewhat modern design. The sliding doors feature bamboo paintings.

Are you familiar with the role of tsukaiban? Originating in the Sengoku period, they were messengers and inspectors on the battlefield, often dealing with enemy negotiations.

Their duties continued into the Edo period, where they were important figures in the shogunate and domains. At Kawagoe Castle, the tsukaiban stayed in this room, relaying orders and supporting daily governance.

Bantou referred to those effectively retired from active duty.

The sliding doors here are plain, reflecting the room’s modest and simple design.

Monogashira means commander of ashigaru (foot soldiers). These were mid-ranking military officers, akin to modern sergeants or section chiefs.

This room is also simple and clearly meant for practical use, not hospitality.

Proceeding down the corridor, you’ll find a courtyard.

On the south side of the Honmaru Goten once stood the grand Ōshoin, or great hall.

Unfortunately, it was dismantled in the early Meiji era, and no longer exists.

However, remnants like mortise holes can still be seen in the southern columns—traces of the original construction. Observing them offers a glimpse into the past.

The garden is beautifully maintained and very calming.

Walk along the sunlit corridor…

You’ll arrive at the Meiji Wing (Exhibition Room 1).

A structure from early Meiji, the Meiji Wing is documented in an 1896 drawing of Miyoshino Shrine’s grounds. It likely supported the Honmaru Goten during its use by Iruma Prefectural Office and Iruma District Assembly.

During 2008 renovations, it was confirmed that its ceiling framework reused materials from the former Ōshoin and other Edo-era buildings.

Historical timbers were preserved as much as possible, with damaged columns carefully reinforced.

This room features exhibits on the preservation and restoration of the Honmaru Goten.

By 2008, the building had weathered 40 years since its 1967 repair, with damage like leaks and cracks becoming prominent.

A two-and-a-half-year restoration began that year.

A semi-demolition repair was performed—stripping the building to its framework, then restoring it with damaged parts repaired or reinforced.

Both traditional and modern techniques were used, befitting its status as a cultural asset.

Damaged wood was replaced selectively, roof tiles checked individually, and even earthen walls were recreated using the original soil mixture.

Today, these efforts are documented inside the exhibition room, offering an up-close look at the charm of wooden architecture.

Japan’s ability to preserve historical buildings while blending tradition and technology is truly impressive.

The oni-gawara here is a decorative tile replaced during the restoration. Originally, there was no oni-gawara on the south side due to the presence of the Ōshoin.

After it was dismantled, one from another building was reused. The resemblance to the north side’s tile supports this theory.

Feel the weight of history in its details.

This is the original roof base, made using the doibuki technique—overlapping thin cypress planks to form the base layer. It’s a highly skilled traditional method.

Even unseen parts reflect the master craftsmanship of traditional Japanese carpentry.

Now, let’s exit the Meiji Wing and continue on.

In the Edo period, “monks” referred to Buddhist priests. This was their room.

It now serves as Exhibition Room 2, displaying various materials.

It’s a tranquil space where you can take your time.

The courtyard surrounded by the monk room, the chief retainer’s office, and back corridor has a wonderful atmosphere.

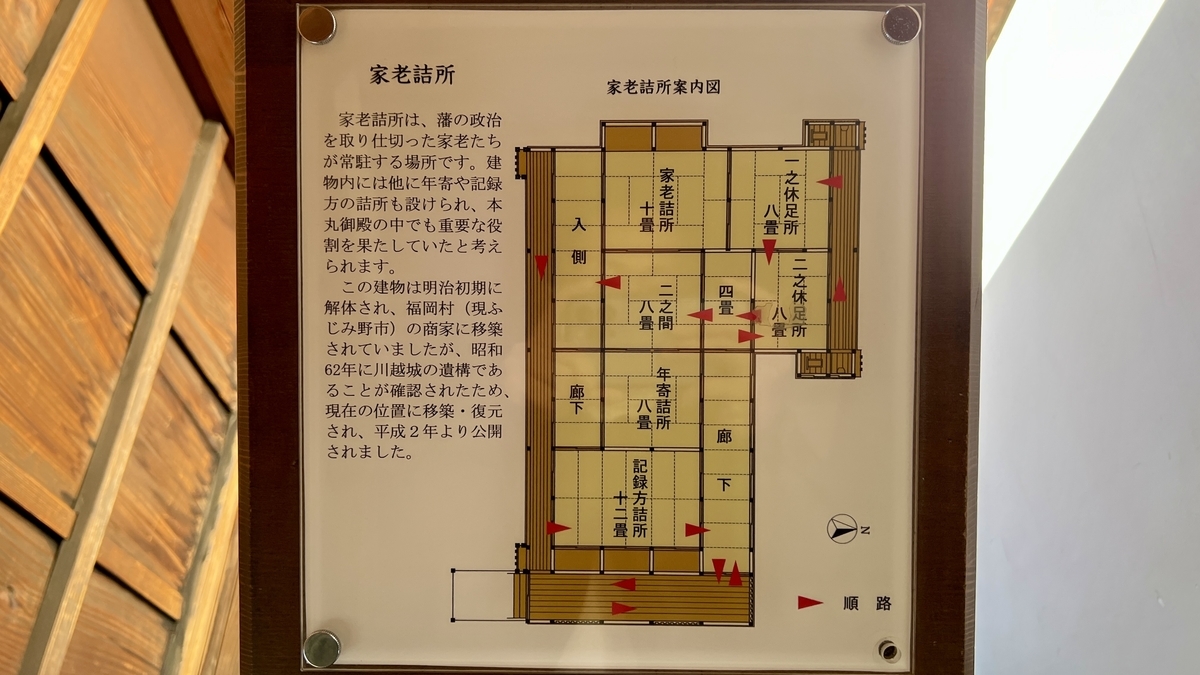

The chief retainer’s office was where the karō (senior retainers) of Kawagoe Domain handled political affairs.

In the Edo period, feudal lords were often in Edo for alternate attendance, so domain administration was left to the retainers.

This building was dismantled in the early Meiji period and rebuilt as a merchant house in what is now Fujimino City. In 1987, it was donated back to Kawagoe City and relocated here.

A rare piece of history passed down through generations.

Sunlight streams into the corridor toward the courtyard, enhancing the mood.

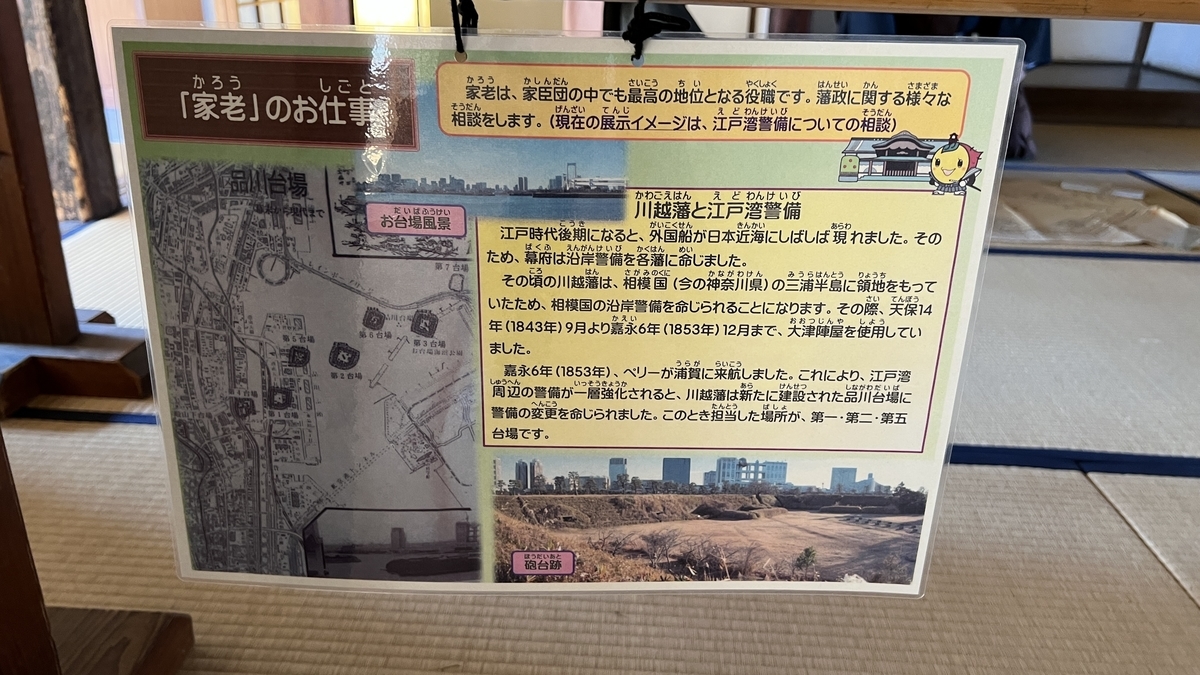

The dolls here depict a discussion among retainers about how to handle coastal defense following the arrival of Perry’s black ships.

Detailed explanation of how shutters were locked in the past. Quite clever.

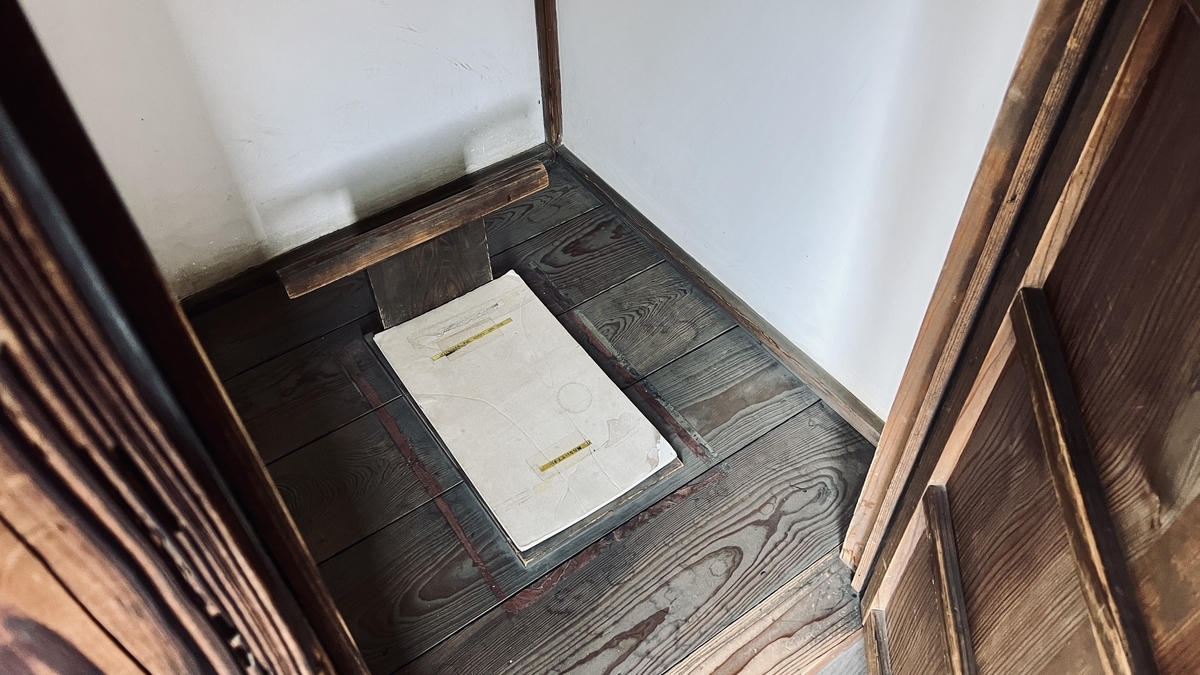

As the Honmaru Goten hosted many people, toilets were installed throughout.

Most extended outside the building, but some, like the one in the retainer’s office, were inside.

This reveals much about daily life and architectural ingenuity of the era.

Exit the retainer’s office and continue toward the end.

Compared to the main entrance, the Nakano-kuchi gate is smaller but worth noting.

It’s about 2.5 ken (approx. 4.5 meters) wide and has a more subdued design.

Originally topped with a chidori gable, the current flowing roof was added during 1967 repairs.

Traces suggest it once protruded northward by 1 ken and featured steps and a formal dais like the main entrance.

These clues speak volumes about the architectural style and formality of the time.

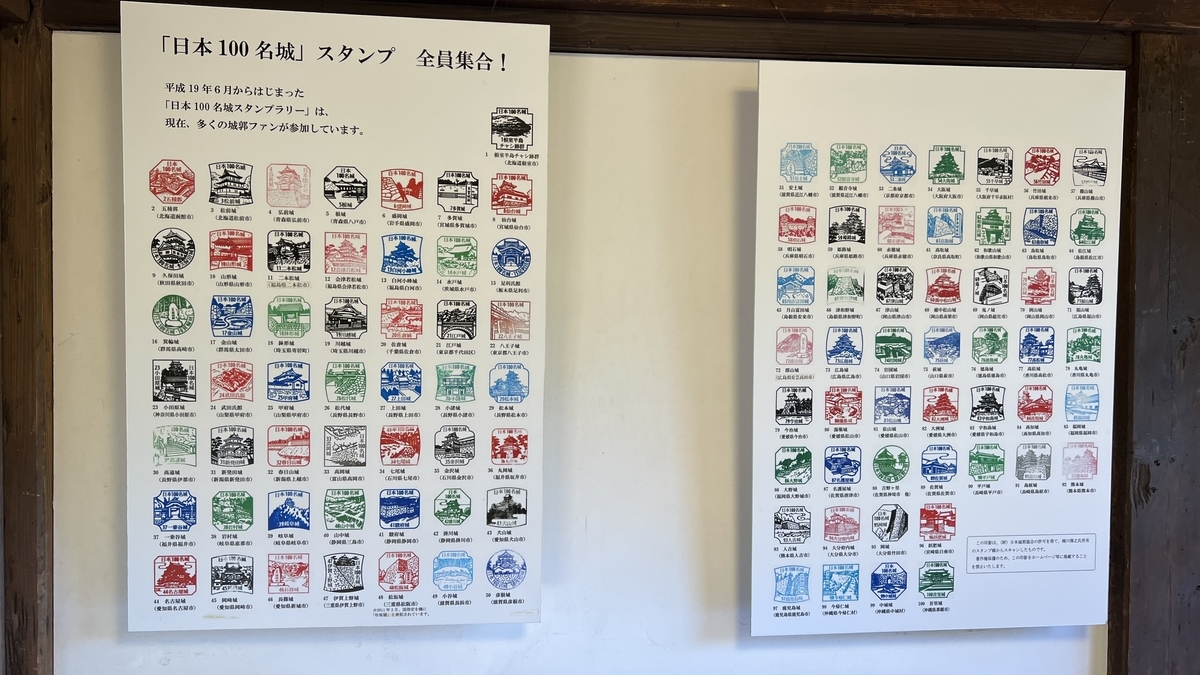

Also displayed here is a model of Kawagoe Castle.

The foot soldier room was where guards stationed themselves.

Kachi (foot soldiers) were lower-ranking samurai who fought on foot.

Unlike mounted warriors, they acted as guides in battle and guards in peacetime.

They held samurai rank and were distinct from ashigaru (infantry).

They also served mid-level administrative roles in domain governance.

The Great Hall spans 36 tatami mats, the second-largest room. Visitors likely waited here for an audience with the lord, which took place in the now-vanished Ōshoin to the south.

The sliding doors feature pine trees—it’s the most ornate room.

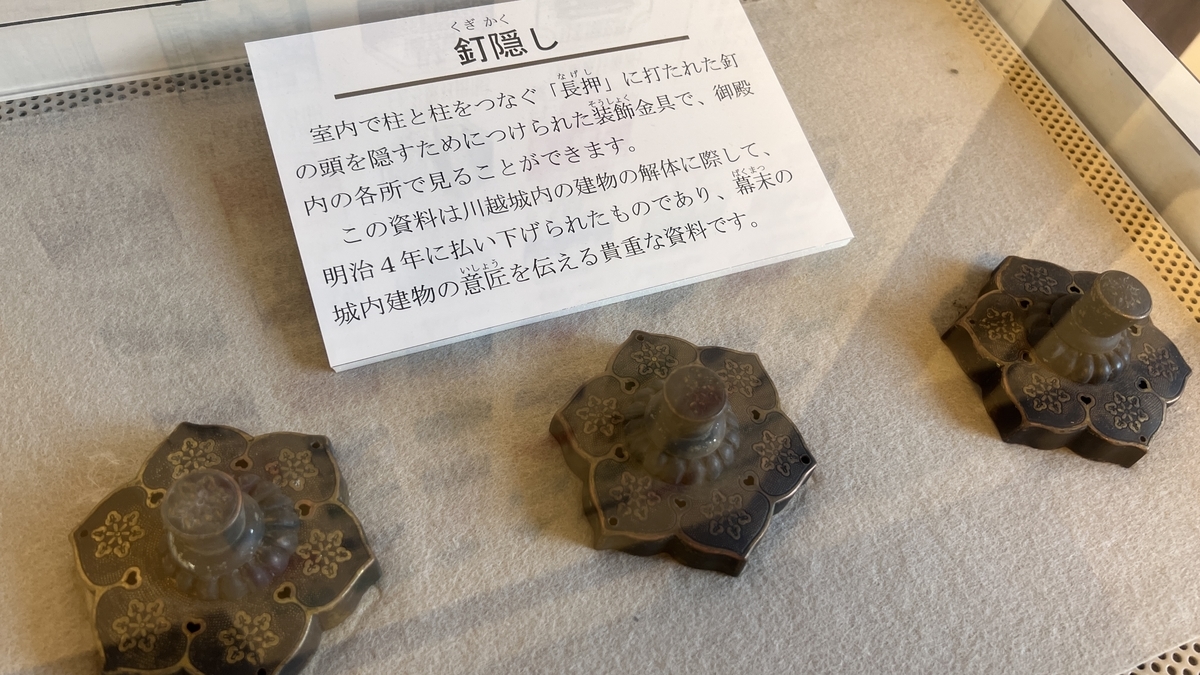

Even the nail covers are luxurious.

Also displayed here is a purple-suso-odoshi armor, a richly colored traditional suit.

Interestingly, this room was once used as an indoor sports facility. Volleyball marks still remain on the ceiling.

The historical value of such places is often recognized more deeply as time passes.

Only two Honmaru palaces remain—this being one—but the volleyball traces make it uniquely memorable.

And with the entrance in front of the Great Hall, your tour comes full circle.

Only two original Honmaru palaces remain: Kawagoe Castle and Kochi Castle.

This makes Kawagoe Castle Honmaru Goten an incredibly rare historic site.

Its impressive entrance and grand hall befit a palace that welcomed shoguns.

Come and experience its history firsthand.

(Duration: Approx. 40 minutes)